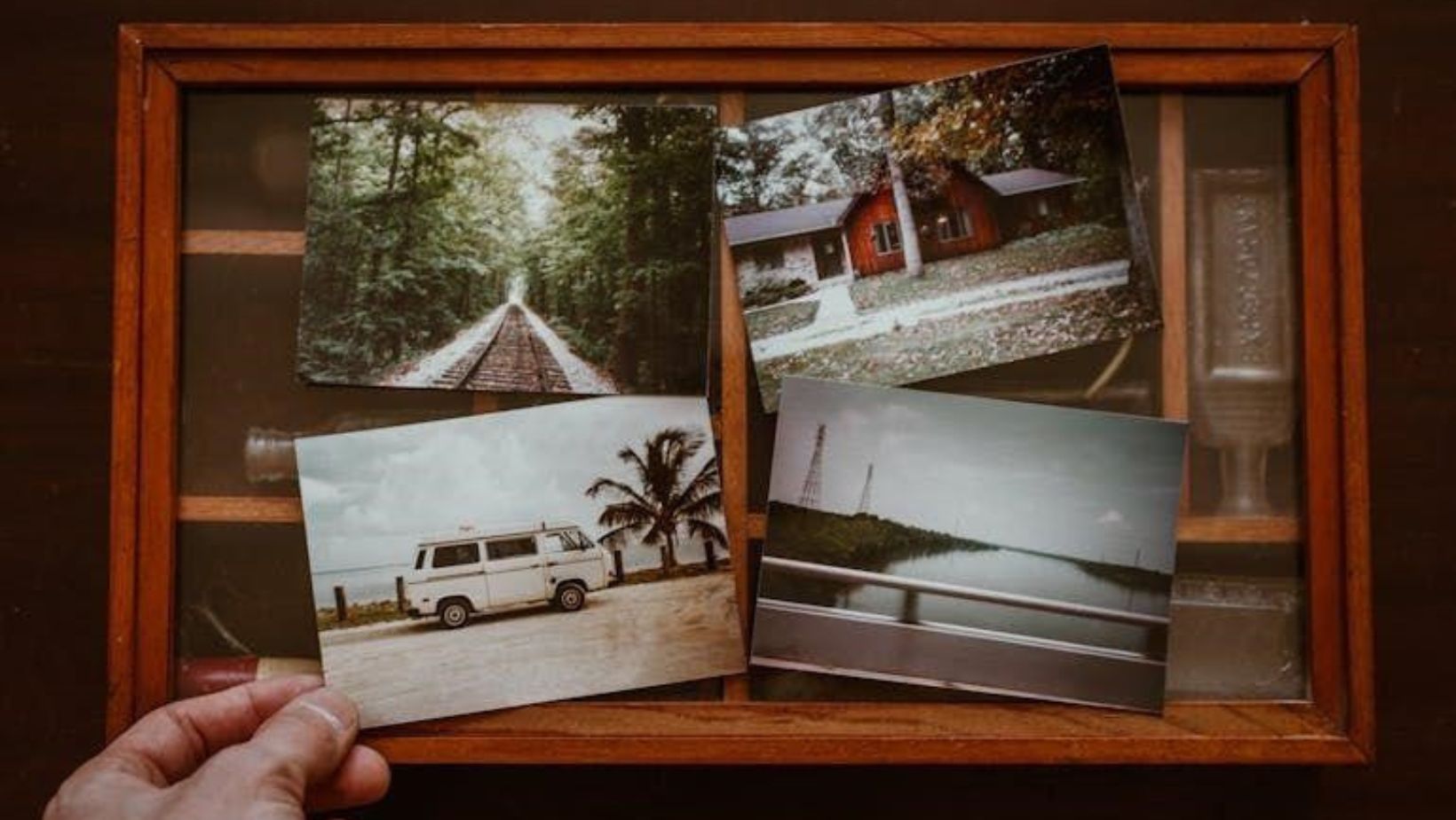

Sometimes, you only notice a place has changed when you flip through old photos. A valley that used to stretch wide and green. Or a coastline with more sand than water. And any eco-friendly city-dweller can tell you how much their cities have changed over the past few decades. With all that change, that cracked snapshot from a dusty box starts feeling heavier somehow. It reminds you that the world used to look different—and that someone was there to see it. Preserved images can speak for disappearing landscapes in a way that words often can’t. They carry the quiet weight of proof.

Faded Grasslands, Shifting Shores

There’s something strange about standing on a cliff edge that’s moved fifty feet inland. The ground looks solid enough until you remember where it used to be. It happens fast sometimes—faster than you’d think. Glaciers that spanned the skyline thirty years ago are now just streaks of ice. Rivers shift. Forests dry out. Beaches shrink. Picturing this, you feel like an ancient wizard of conservation.

You might not always notice these things on your daily walk, but photos do. The tourist snapshot from the 70s. Your aunt’s Polaroid from a family hike. A kid’s birthday party with the mountain range in the background. These aren’t just old memories. They’re anchors in time, showing what used to be normal before it slipped away.

Archives of Memory: What Gets Saved and Why

Plenty of people treat photos like clutter. Boxes full of old prints, stacks of slides, dusty albums that no one opens. But those stacks might hold the only visual record of a local wetland before it got drained for development. Or a desert before drought turned it to cracked stone.

Museums recognize this value. Institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum have increasingly acknowledged the importance of photographs as historical information-bearing resources, not merely as art objects. This shift underscores the role of photographs in preserving cultural and environmental histories.

Elders in small towns and the kids who inherit shoeboxes full of images they don’t recognize also understand their worth. Each of those pictures is a tiny window, providing context to stories that might sound exaggerated without them. Photos ground oral history and help communities remember who they were and what their land once offered.

Sometimes, all it takes is comparing two snapshots from different decades to feel the loss. That’s when preserved images can speak for disappearing landscapes with clarity. You don’t need a degree in environmental science to see what’s gone.

Preserved Images Can Speak for Disappearing Landscapes: Digital Lifelines for Vanishing Scenes

Photos don’t last forever. Ink fades, paper weakens, mold creeps in—and when these images disappear, so do the last witnesses to places already transformed or lost. In the face of climate change, land development, and environmental degradation, physical photographs—family albums, field documentation, community snapshots—carry more than memories. They capture irreplaceable evidence of landscapes as they once were.

These visual records are more than sentimental keepsakes; they’re proof. Proof of how land has changed. Proof of what once grew, stood, and thrived. Preserving them isn’t just about nostalgia—it’s a form of environmental testimony and cultural preservation.

That’s why digitization plays such a powerful role. Converting physical photographs into durable digital formats allows them to be archived, shared, and used for research, advocacy, and public awareness. Without this step, the stories held in those fading images risk being lost alongside the environments they document.

As a trusted digitization service, Capture supports this urgent work by helping individuals, families, and communities convert fragile photos into high-resolution digital files. Their platform offers more than convenience—it creates accessible archives that can travel, inform, and endure. Whether used in climate studies, local exhibitions, or intergenerational storytelling, these digitized records strengthen our collective ability to remember and respond.

After all, preserving what’s left isn’t just about holding on. It’s about connecting across time, distance, and purpose. Every scanned image ties a thread between what was, what is, and what still might be saved.

Looking at What’s Gone: Proof and Protest

Preservation and sustainable living aren’t always passive. Sometimes, a photo becomes a protest. Think of rephotography projects where someone stands in the exact spot where an old photo was taken and captures the current scene. The contrast is often jarring. It stirs something. A calm lake now covered in cracked earth. A thick forest was replaced by concrete.

People have used these image pairs to fight back. To challenge city planning and push for environmental protections. To remind others that change doesn’t always mean progress. The visuals tell a story that data alone often fails to convey.

Photos taken without an agenda become some of the strongest evidence, especially when preserved images can speak for disappearing landscapes with unfiltered clarity. No captions are needed. Just a visual before-and-after that won’t let you look away.

Personal Landmarks in a Vanishing World

Everyone has one spot that’s burned into their memory. A swimming hole from childhood. A meadow that always had fireflies. A hill where the sunsets felt endless. It doesn’t need to be iconic or dramatic. Just yours.

Now think about how it’s changed. Maybe the water dried up, or maybe trees were cleared. Maybe there’s a gas station there now. If you’re lucky, you’ve got a photo. If you’re really lucky, your family has it, too.

That photo might not mean much to anyone, but it’s part of a larger puzzle. When taken together, these personal images form a grassroots record of how the world has shifted. They’re time-stamped truth. So, open those drawers. Go through those boxes. What might you find in there that deserves a second look?

Holding Onto What Matters

The world changes faster than we think. Landscapes disappear quietly until someone holds a photo and says, “Look. That used to be here.” That image might be the only reminder that a place once had water, trees, birds, or people. It might be the last record of a shoreline before it sank or a forest before it burned.

Preserved images can speak for disappearing landscapes with a power that memory alone can’t match. They don’t just show us what was. They challenge us to ask what still matters enough to keep.

So dig out your old photos. Get them scanned. Share them. Talk about them. Make sure they’re more than just pieces of paper in a box. Because someday, someone will need to know what the world used to look like. And you might be the only one who can show them.